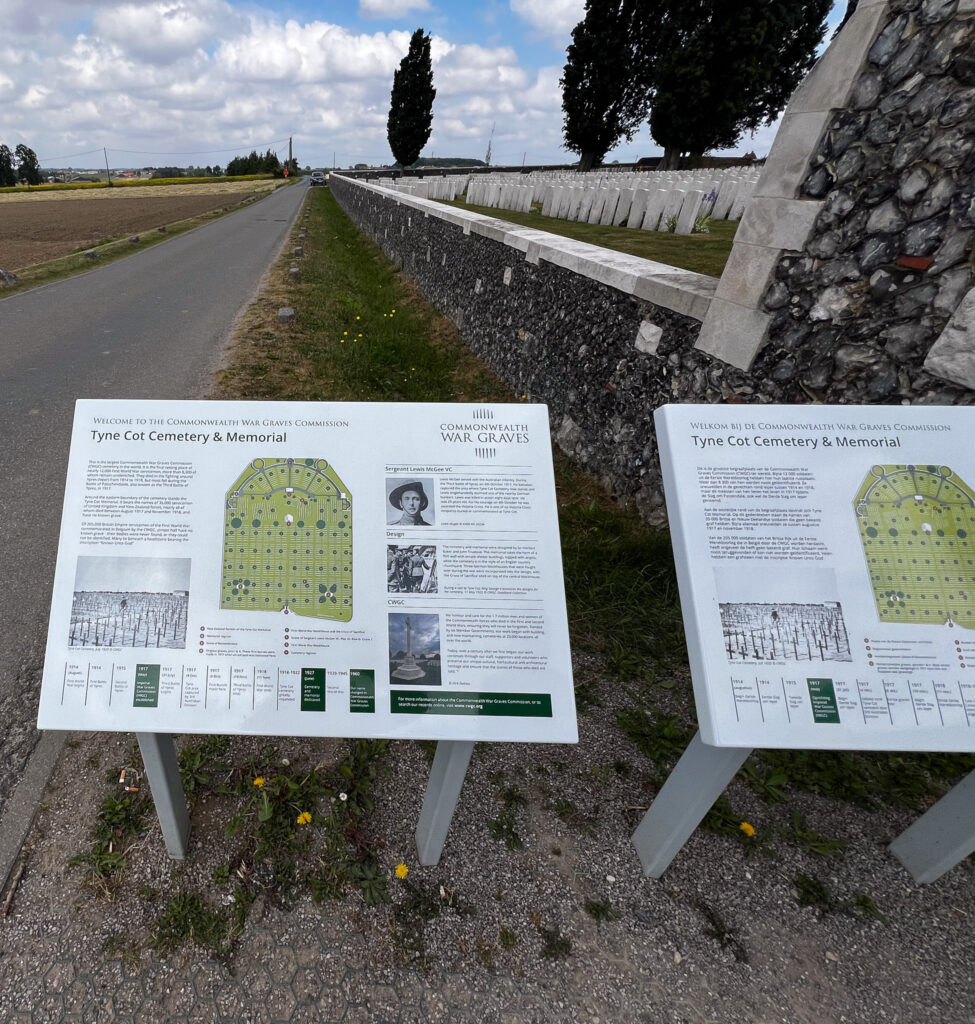

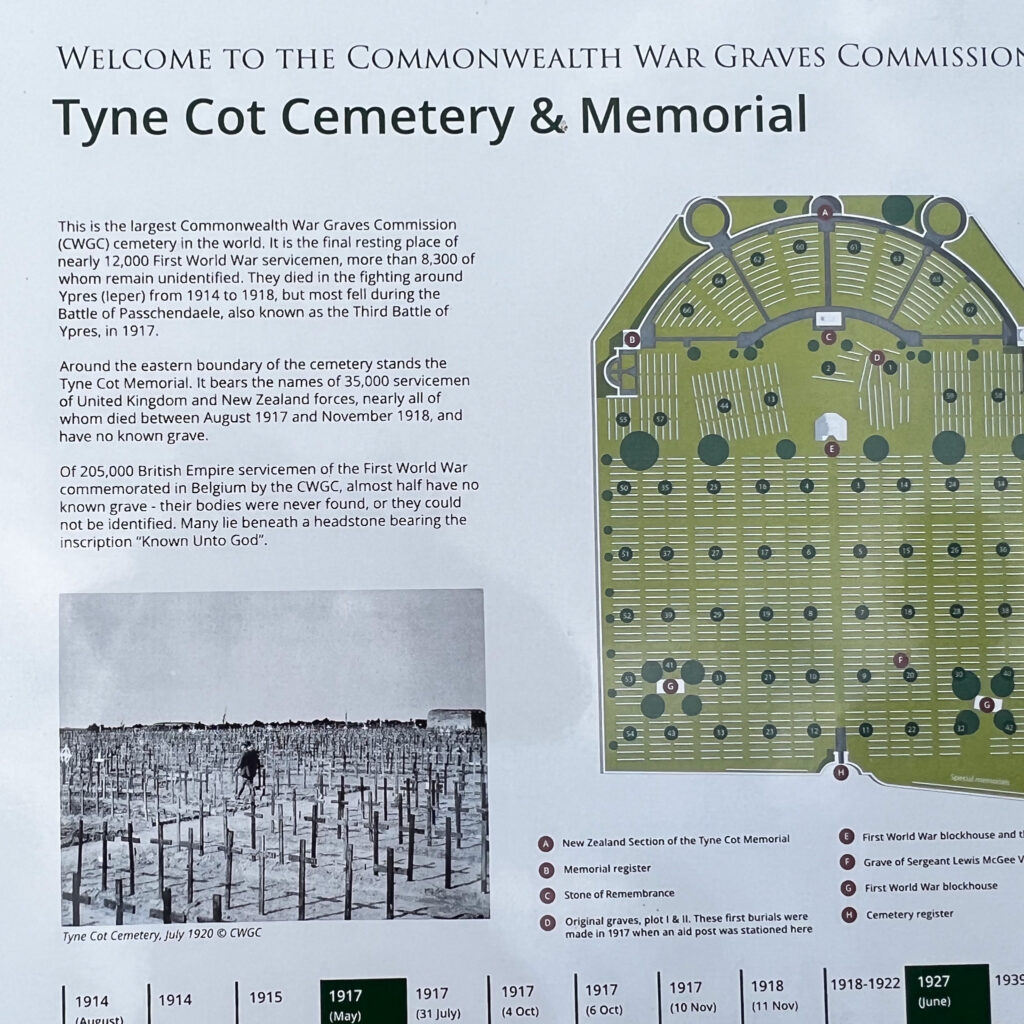

Although our ride from Lille to Ypres was a short one – 43 km – it involved a very important stop at the Tyne Cot Cemetery and Visitors’ Centre, at Passchendaele. This was the site of the famous “Third Battle of Ypres”, July to Novemer 1917. It is the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery in the world and it seems appropriate, now, to talk about the role of that organization.

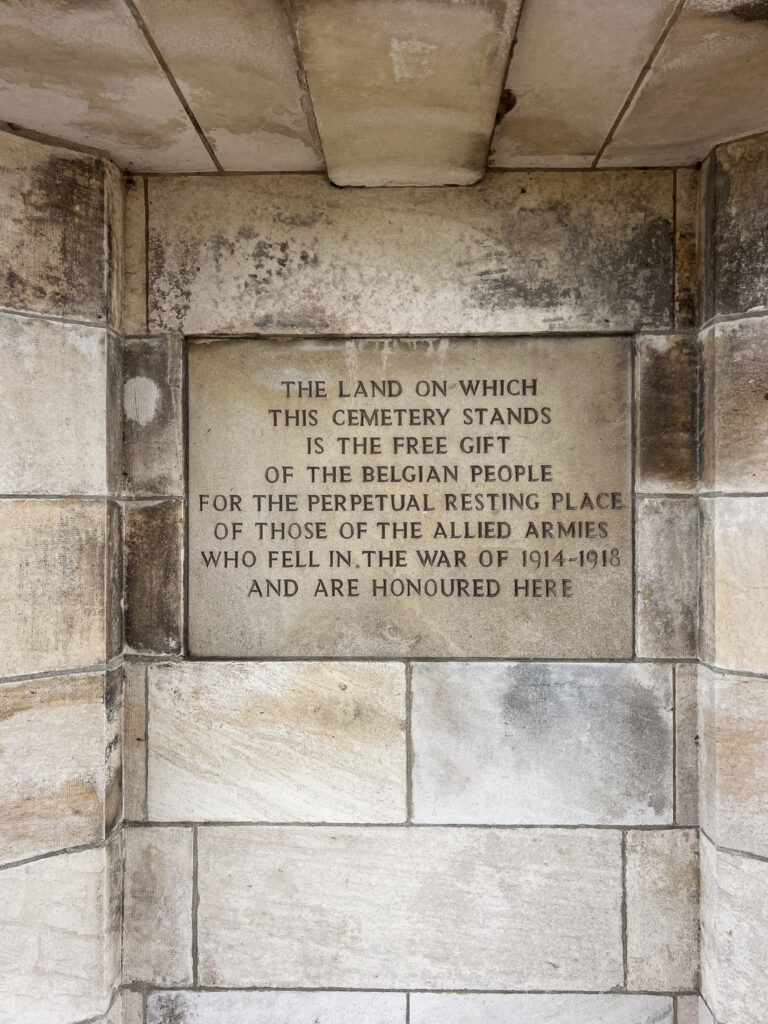

“In late 1914 a Red Cross unit led by Fabian Ware began to record the burial places of British Army soldiers. Its work was recognized by the military authorities and became the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries. In May 1917, the Imperial War Graves Commission was founded. The organisation’s first responsibilities were to register the dead, build cemeteries and mark the graves of fallen soldiers, and construct memorials for those with no grave.

Its founding principles were that all should be treated equally regardless of rank or class.

Since 1960, it has been known as the “Commonwealth War Graves Commission”. (“CWGC”.) Today the CWGC is responsible for the commemoration of 1.7M men and women who lost their lives in service with Commonwealth forces during the two world wars. It cares for graves and memorials in 23,000 different places in more than 150 countries.”

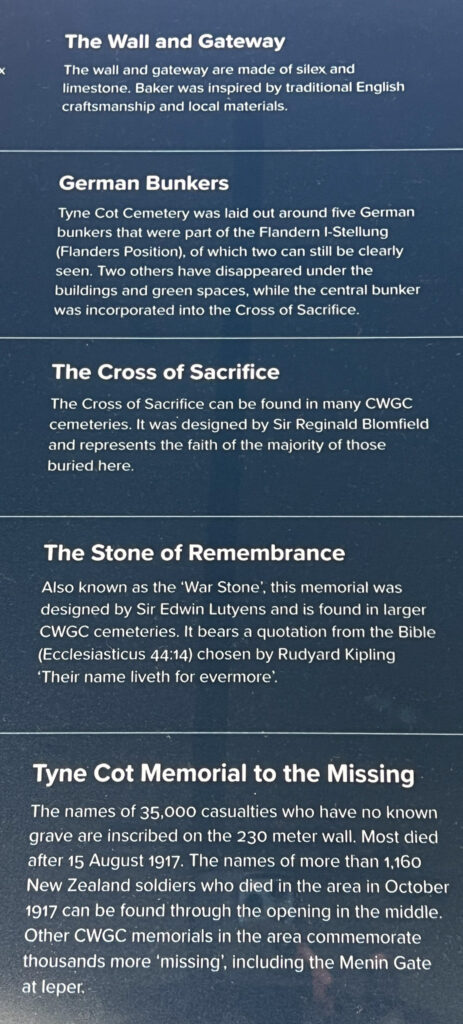

As mentioned, “The Tyne Cot Cemetery (Passchendaele) is the largest CWGC in the world. There are almost 12,000 graves, and a memorial wall bears the names of 35,000 more soldiers who have no known grave. (They are also commemorated on the Menin Gate in Ypres. More on that later.) Most of those commemorated at Tyne Cot died during the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as ‘Passchendaele’.”

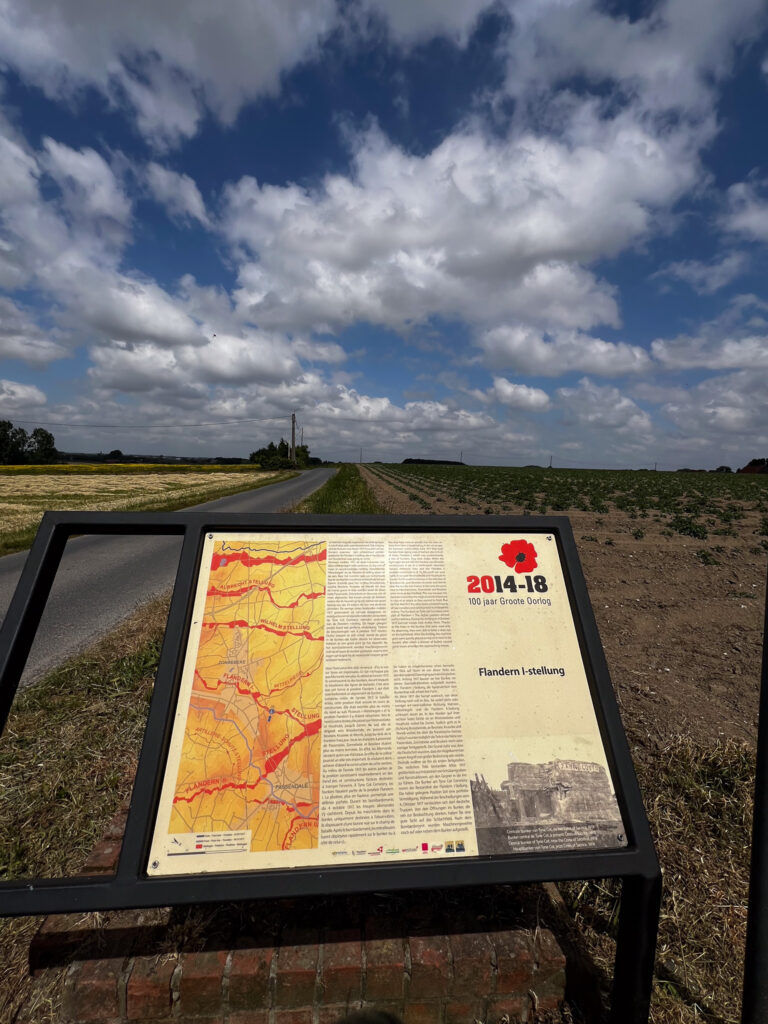

The cemetery itself was “laid out around five German bunkers that were part of the ‘Flanders Position’ of which two can still be clearly seen.” (See the photo.)

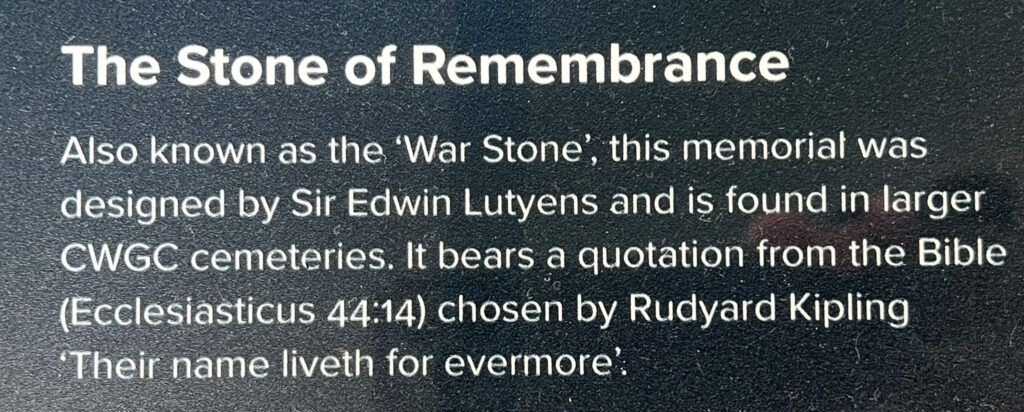

“Their name liveth for evermore.” Rudyard Kipling.

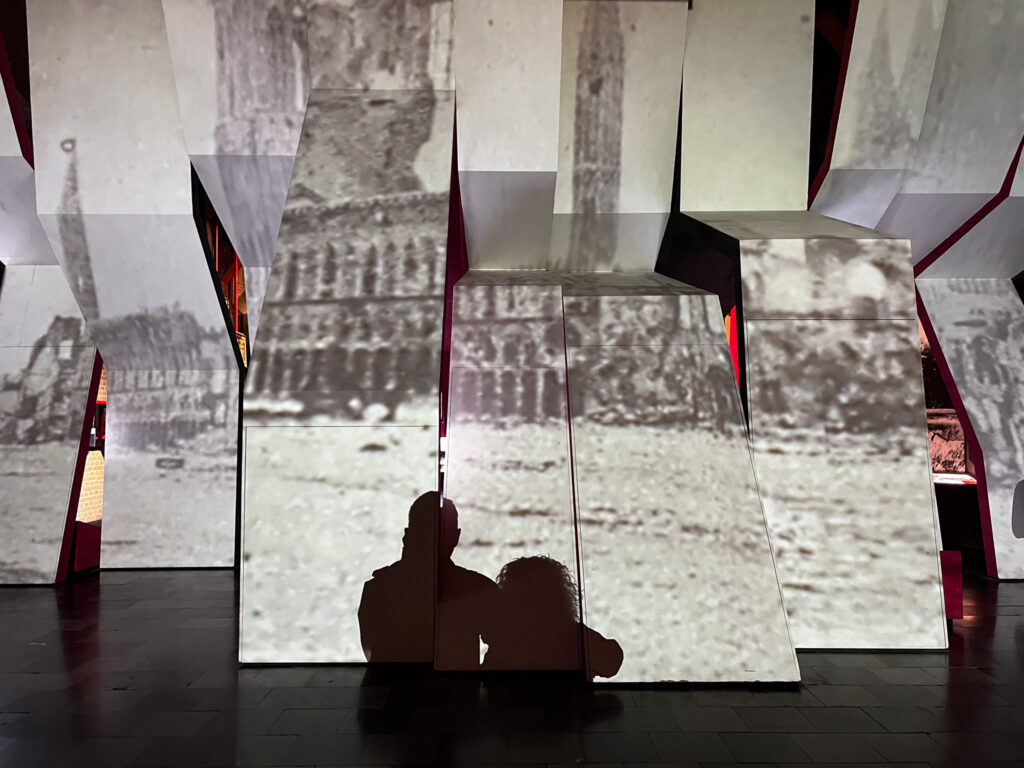

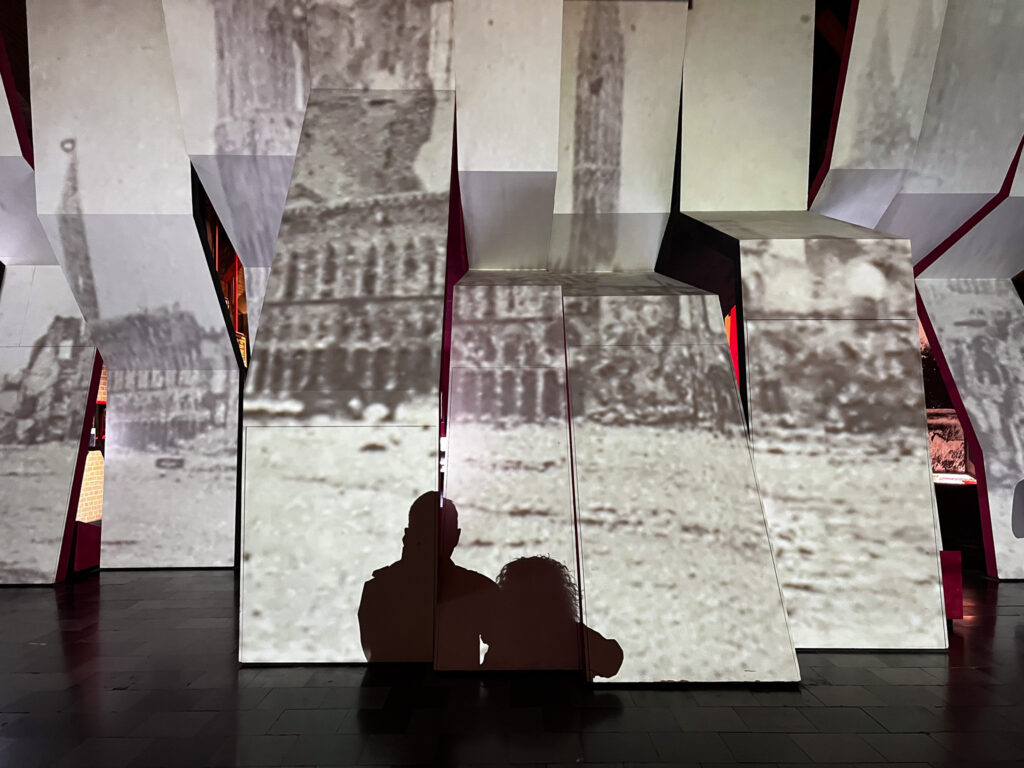

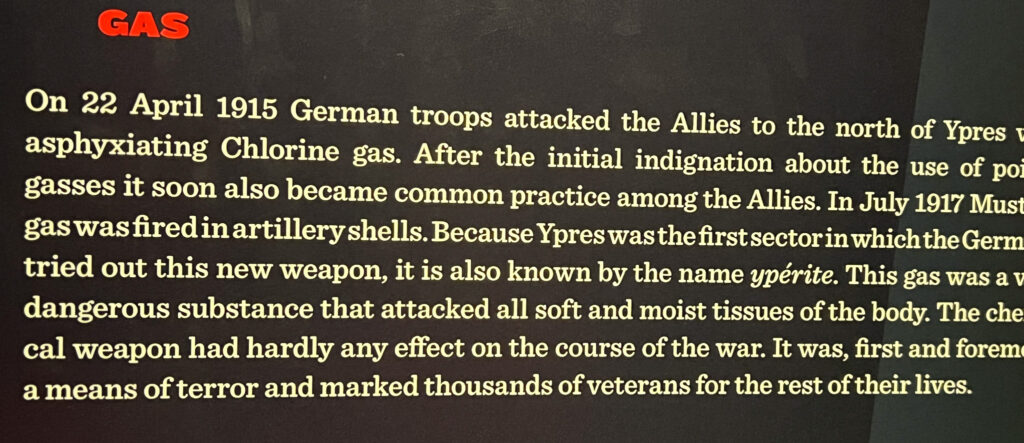

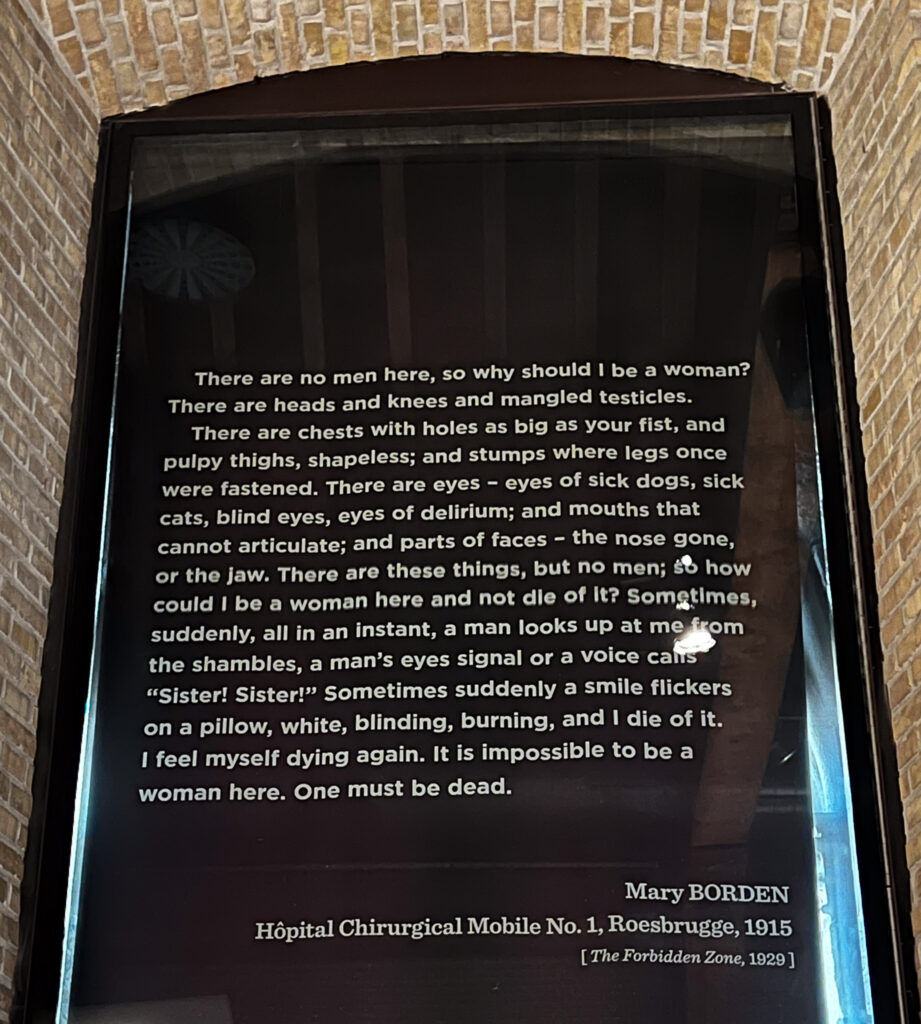

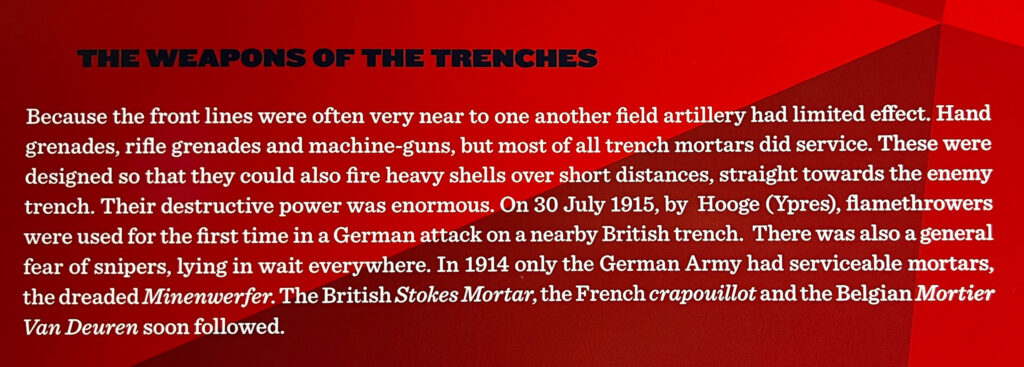

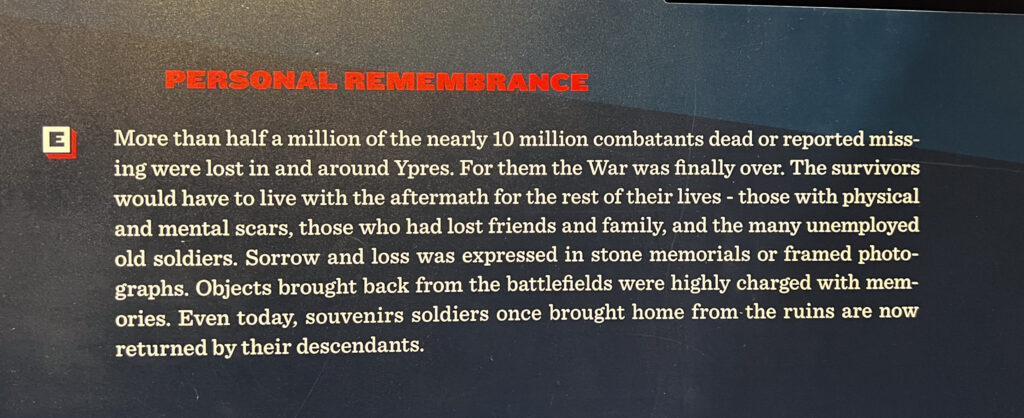

Understandably, we had a quiet ride into Ypres, dumped our gear in the hotel and walked into Ypres’ beautiful town square where we visited the “In Flanders Fields Museum”. It is in a beautiful old “Cloth Hall” building, the exhibits have been thoughtfully curated, and we learned a lot. For example: it was at Ypres on April 22, 1915 that the Germans first used chlorine gas as a weapon and in fact, the gas was referred to as “Yperite”. Although the use of gas had hadly any effect on the course of the war, it was used first and foremost – by both sides – as a means of terrorizing soldiers and “it marked thousands of veterans for the rest of their lives”.

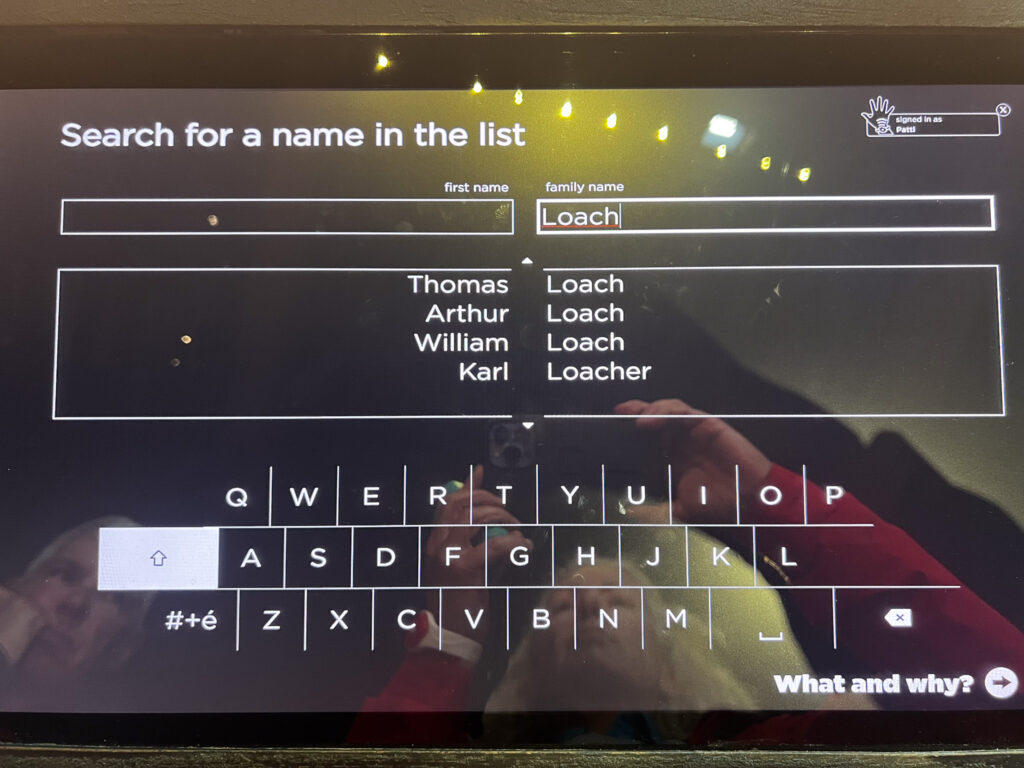

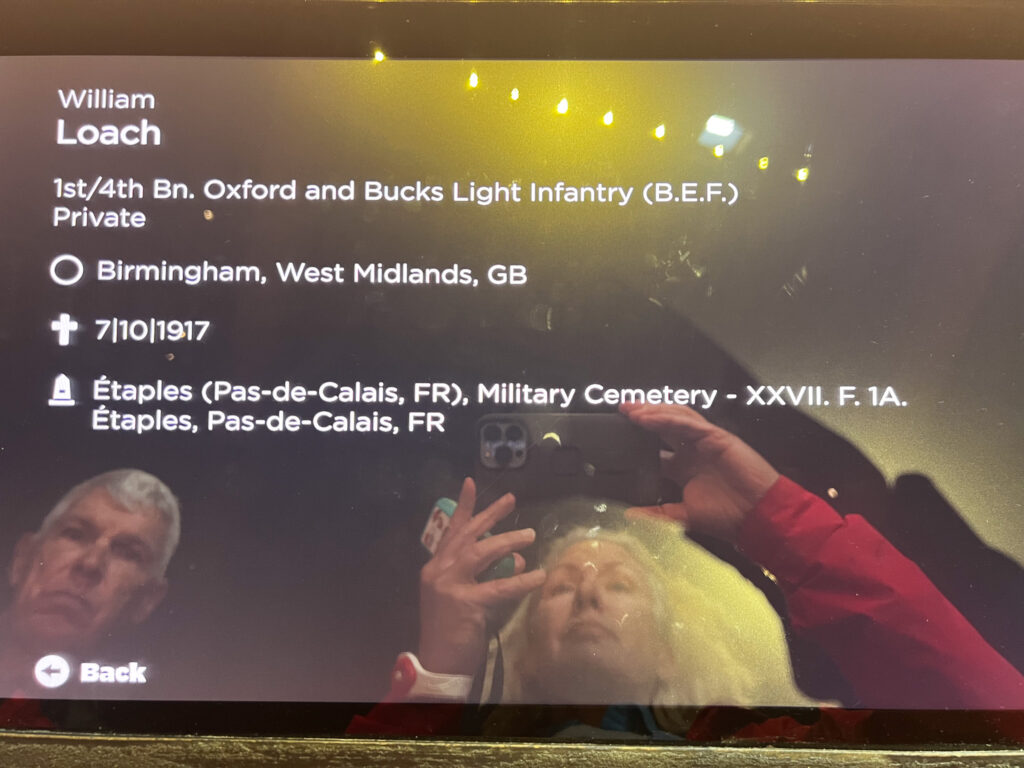

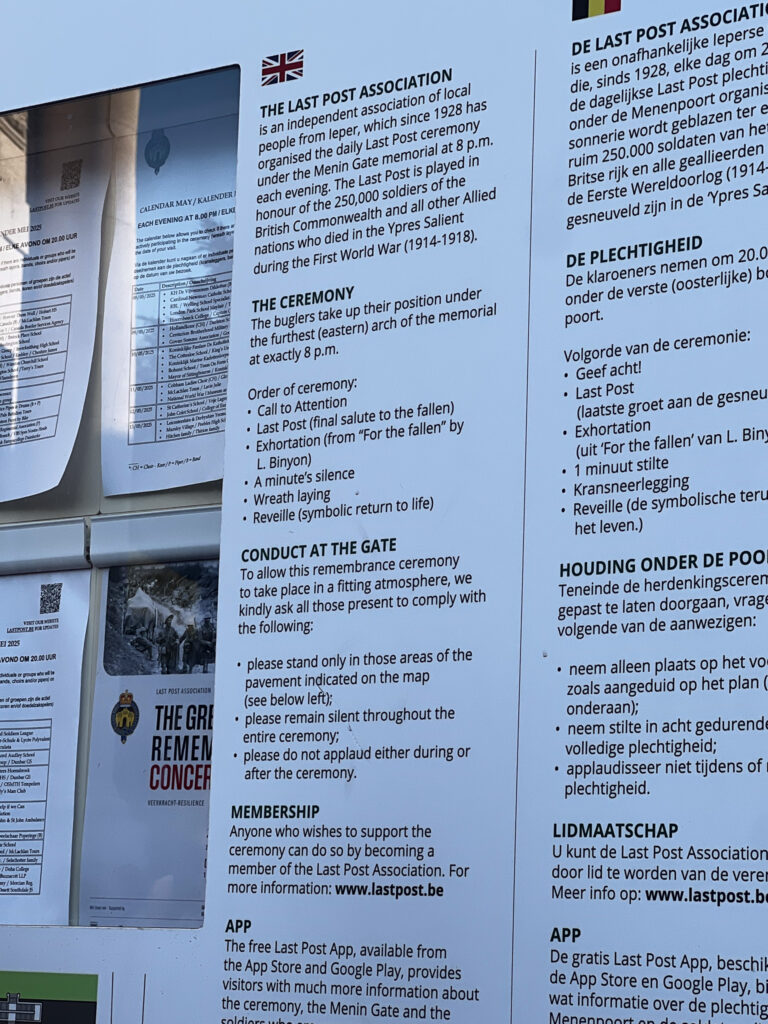

The night before we arrived in Ypres we had read about a nightly occurrence that has happened there 365 days a year, continuously, since July 2, 1928, i.e. 33,601 times: the playing of The Last Post and Reveille at the Menin Gate. (The names of thousands of fallen soldiers who have no known graves are inscribed on the inside of the gate.)

At 7:45 we stood in a huge crowd (mostly men), silently, patiently, waiting. We happened to be within 5 feet of the “marshall” and he made sure everyone was where they should be when the buglers made their way through the crowd. You can see the order of service in the photos, above, and the expected behaviour. (“No applause.”) It was respectful. I think we both gasped out loud when a solo piper was joined by a full pipe band and drums. I don’t know if I will ever be as moved as I was by that ceremony, in Ypres.

After the crowd dispersed, we made our way to a Persian pizzeria (don’t ask, it was delicious), then back to the hotel, to call it a day. Our Passchendale/Ypres experience couldn’t have been more perfect.

*If a soldier’s remains were found after their name had been inscribed onto a CWGC monument, a marker would be placed beside their name – in this case, a small red metal poppy – to indicate to the observer that the soldier’s gravesite could be found in the CWGB’s records.

Well this had to be the icing on the cake. Oh the pipers! Love them. Bless all those souls gone but not forgotten.

0

0